Yes, folks, it's that point in the foot surgery recovery period when I'm purportedly "okay to go outside," but still so intimidated by the idea of placing my swollen gashed-up foot on the black-iced Brooklyn pavement that I'm using any excuse I can to remain inside. It's true - I'm a prisoner of my mind. There are also very few socks that will fit comfortably over my stitches. Which is too bad 'cause I really need band-aids.

The excuse today is - "I have to write!" But since I'm not sure that what I really want to write is printable, I will satisfy my urge to share by digging back into my creative nonfiction catalog. Please bear with me.

"Poster Child" was composed in 2006 or so, which makes it and me incredibly old. I'll only put a chunk of it up here since it's long, and if I'm feeling brave, will publish the rest in subsequent chunks. Many times I've tried to get it published by someone else. Now that I'm publishing it myself, I'll look for a fat paycheck in the post signed by Eli James.

It's about a teenager and me and my two court appearances.

Poster Child (part one)

by Eli James

I moved to New York to restart the rock band I had started in Philadelphia before I got sick of living there. I didn’t bring any musicians with me up the Jersey Turnpike, so I had to begin recruiting from scratch. It wasn’t until two years later that I comprehended the basic facts apparent to the more seasoned New York band starters: that good rock drummers charged $200 per gig and $100 per rehearsal, and that the free ones were flakes or alcoholics or homeless, or worse, not super at keeping time. But because I hadn’t learned this yet, I thought the world was picking on me, blighting me with delinquent drummers, stunting the growth of my newest most awesome artistic project since I wrote that play senior year about Lewis and Clark. This was really going to blow the world away, and it was going way too slowly.

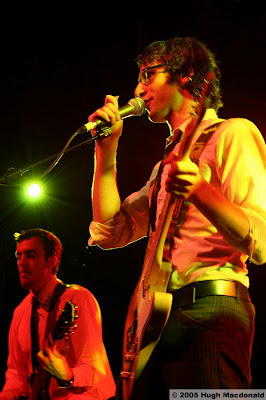

After my first three drummers quit or disappeared or were fired for chomping too much lithium, I found a nice young man who looked like he might stick around for a while. Jason was only mildly alcoholic – meaning that at worst his pre-show tequilas made him drum faster, not slower. Three months later he would quit, telling me he wanted to start training for a marathon. This was a whole new take on drummer-flaking that I still applaud to this day for its originality. However, when I first got my hooks in him, I immediately put the feelers out for a gig – hoping to land a show before another wave of drummer misfortunes could darken my door. I stuck my CD in a black plastic folder, slammed a sticker on the front of it, and managed to intercept one of the myriad Tuesday-at-ten slots the city’s web of midlevel booking agents were hungry to fill. It was at The Continental on Third Avenue. I think that’s where every band in New York plays for the first time. Like the great CBGB’s, The Continental no longer exists. Also like CBGB’s, its reputation for being great had faded away at least twenty years before.

It was my first show in New York as a New York resident. I had to figure out how to get New York people to attend. I knew nothing about the city’s street-team culture, the ins and outs of sticking posters on walls, but I reasoned it couldn’t be as complicated as the drummer-finding process that had nearly killed me. Little did I know that the politics of grassroots band promotion were fraught with dangers that would make assembling a rock group seem like a meditation.

I’d previously lived and played in Philadelphia and Los Angeles. I wondered if it was possible that New York was the same, in that the only people who showed up to gigs were those who knew somebody in the band, or if the big city was different, if people here were so overflowing with energy that they spilled into clubs at all hours to hear bands they’d never heard of – forced off their paths by the narrowness of the sidewalks, moved by a need to be ahead of the buzz, higher on coke and other drugs than you could be anywhere else.

The first thing that stood out to me about my new hometown, the East Village, which I later learned distinguished it most from the Upper West Side, was that there were posters everywhere. Not just in the doors and windows of clubs, but on walls, telephone poles, traffic lights, and sometimes plastered to the sidewalk beneath my feet. Rarely did a night go by that I didn’t drift off to sleep muttering “Washer-Eye” or “The Rickshaw Thieves,” or “Ref-Sleeper,” words that stuck in my head in those solitary hours like the melodies from commercial jingles. They weren’t really good names. In fact, they were irritating. The only reason I remembered them against my will was that they belonged to those bands that had as many posters as there were bus stops on Second Avenue. Proof that, even on this low-budget level, advertising worked.

The story of my advertising campaign, a product launch that ultimately put me twice before a New York judge, requires a glimpse into the relationship between me and Tommy McBride. Tommy, my bass player and a junior in high school, had responded to an ad I’d placed on Craigslist when he was seventeen and I was twenty-seven. This was what stuck in people’s minds most whenever we played, the fact that I had a very young bassist, who looked closer to twelve than seventeen. He had white freckled skin and a baby-fat belly. He wore Diesel jeans and T-shirts with the names of bands I hadn’t heard of, probably because I was too old. His standout feature was his hair—an orange out of a crayon box, a blinding copper that would be a liability to most, but for Tommy was just another instrument for him to play. He whipped it around to the stops and starts of our songs, twirling it like a whammy bar, refracting and tearing the beams of the lights until a blood-red sheen covered the stage. He remained in the band through all eight drummers.

He came from loads of money, went to a fancy prep school, and spoke five languages—one of them was French, and three were either dead or extremely marginalized. At the time of our first rehearsal he was studying for his ancient Greek final. At lunch he spoke a whole sentence in Welsh. When he stood idle, he put one hand on his belly and one arm over his head. I called it his rock star pose.

Money and growing up in New York City had made him mature beyond his years. His parents let him stay out all night, take trips with his girlfriend to Venezuela, and chip in the same amount of money I did to keep the band going. They were both doctors who ran a hospital on the Upper West Side, Tommy’s dad the anesthesiologist who had overseen Bill Clinton’s heart surgery. The McBrides sent their boy to Riverdale Country School, an elite prep academy in the upper Bronx, what I thought of as New York’s Eton. “I’m one of three non-Jews in the whole school,” he would often say—usually in an effort to bridge some of the gaps in our cultures. He wanted me to know that virtually all of his friends were Jewish. I believed him, and wished in great despair that the Jewish stereotype of wealth and educational pedigree had graced my family as it had Tommy and his entire Semitic circle. Tommy’s pals and girlfriends were all privileged Jews and occasional Asian Americans. His closest friend’s father owned the distribution company that handled Sean John. Until recently they had played in a punk band together called Naked Osprey. My parents had refused to pay for more than two college applications, and the idea of spending ninety-five dollars on the paperwork for Yale was just crazy talk, so I never did it. My dad drove me to pick up my date for the Homecoming Dance in his Dodge Lancer. Tommy would never have allowed such a thing.

No phone interaction between Tommy and me ever lasted longer than thirty seconds. He would end each transmission with, “I gotta run, my history teacher’s taking me out for coffee,” or “I gotta run, I’m picking up my brother from the Sleater-Kinney show in D.C.” (His older brother.) I was bruised by his brush-offs, but always impressed at the amount of stuff he had going on. He was on the debate team. He was in the jazz band at school and had been recognized as the best upright bass player in the state (high school division.) He tutored the underprivileged in his spare time. That was exactly how he phrased it. “I’ve gotta run. I’m tutoring the underprivileged.”

For long stretches, when drummers disappeared and we had to endure endless rounds of replacement auditions, it was Tommy and I against the world – two unlikely partners working their fingers to bloody stubs, playing chunky riffs for days on end and talking about girls. We shared a complicated relationship, a unique camaraderie based on our love for the early Who, The Wedding Present, and The Jam, as well as the fact that he was seventeen and I wanted to be seventeen. When he first slinked into the audition room hefting an instrument almost twice his size, complaining that “traffic was a bitch on the West Side Highway,” I instantly wanted him to like me. His youth was glaring and garish, and in many ways unbearable, but it was contagious. I wanted to go out with Tommy, get drunk with him, meet his friends, be his study partner for the PSAT’s. I wanted to be immature and silly; give him noogies and friendly jabs in the arm. My teen years had been extremely guarded, while his seemed open to a wealth of possibilities.

To be continued....

No comments:

Post a Comment